So what, better than what, and what type of results?

Search

Google’s new mobile, social media and cloud storage products have made it more omnipresent than usual. That’s why I was surprised to hear Brian Schmidt, Google’s Americas sales director, say that Google still considered itself a search company.

This seemed a little disingenuous at first, just something Schmidt would say to sooth me and the other Online News Association conference field trippers at Google’s Boston office last week.

But then Schmidt explained that everything Google does is “dependent on users opting in and finding value in the experience.” With so much information available on so many different devices (see my New York Times Room for Debate forum commentary on paying for device-based convenience), Google’s success is based on people making a conscious choice to use Google products to find and link them to what they want.

But then Schmidt explained that everything Google does is “dependent on users opting in and finding value in the experience.” With so much information available on so many different devices (see my New York Times Room for Debate forum commentary on paying for device-based convenience), Google’s success is based on people making a conscious choice to use Google products to find and link them to what they want.

“Search” means more than people typing keywords in a little box. “Search” now means “I’m coming to you – and not someone else – to make my life better by finding what I need and connecting me to it.”

Thus, news organizations should be search companies, too. But they’re not going to get there by counting page views and unique visitors. For some news orgs it seems to be a point of pride that the bulk of the visits to their sites start with their all-things-to-all-people home pages. How about defining success with metrics that indicate whether people are finding what they want?

The humanity of web analytics

This snippet from the Economist’s review of Brian Christian’s book about artificial intelligence – The Most Human Human: What Talking With Computers Teaches Us About What It Means To Be Alive – reminds me that web analytics is about people, not data:

“People produce timely answers, correctly if possible, whereas computers produce correct answers, quickly if possible. Chatbots are also extraordinarily tenacious: such a machine has nothing better to do and it never gets bored.”

“People produce timely answers, correctly if possible, whereas computers produce correct answers, quickly if possible. Chatbots are also extraordinarily tenacious: such a machine has nothing better to do and it never gets bored.”

This spring the nine hardy students who took my USC Annenberg web analytics class came up with wonderful insights that could never have come just from reading a report straight from Google Analytics, Omniture or any other chatbot.  Part of their grade was based on whether the (equally hardy) participating news and nonprofit organizations were actually going to use their analyses for decision-making. This meant each student had to really understand the organization’s strategies, goals and personalities before he/she dug into the data. Here are some of the things we learned.

Part of their grade was based on whether the (equally hardy) participating news and nonprofit organizations were actually going to use their analyses for decision-making. This meant each student had to really understand the organization’s strategies, goals and personalities before he/she dug into the data. Here are some of the things we learned.

Content is indeed king, but only if it’s coded

None of the organizations coded site content with enough detail to make decisions about what to do with their sites. Data coming straight out of Google Analytics or Omniture was coded only by date published and by broad categories such as “News.” This is the equivalent of marking a box of books “MISC” – or putting in “stuff” in any search engine.

For example, let’s say an organization believes it can build and engage audiences by adding “more local politics and government coverage.” To track whether it did indeed produce “more,” and what coverage did result in increased visits and engagement, the org needs to track how many politics stories it has, by topic and local geographic area, and how much traffic each topic and/or area gets.

Each student developed a taxonomy of codes the organization could use to classify its content, and then manually (I told you they were hardy!) coded sample data pulled out from chatbots, er, Google Analytics or Omniture.

Track traffic by day, week and by topic, to determine if the site is getting the traffic it should

Many organizations look at monthly data, and celebrate traffic spikes. Hidden in monthly data, however, are clues to where to build targeted audiences and advertisers. Health/fitness section traffic, for example, should increase the second week in January, perhaps fall off after Valentine’s Day (!), and increase before swimsuit season.

More content = more traffic

Looking at visits by day of week, we saw radical drops in visits on the weekends. This seemed to be due to little unique local content being posted on Saturdays or Sundays. In this age of the 24/7 newsroom and increased Internet access through mobile, can news orgs afford to make resource decisions based on non-audience-based, chicken-and-egg logic (“We don’t get much traffic on the weekends so we can’t justify adding weekend staff.”)?

Sometimes you should have separate sites for each audience segment….

Josh Podell, an MBA student, focused on analyzing the e-commerce donation functions on the nonprofit sites. He observed that it’s hard to understand what works and what doesn’t when donors are coming to the site to find out more about the organization but residents are coming to find out about programs and services. Josh’s suggestion: Have a completely separate site – and Google Analytics account – for donors. An org could have much more focused content for each audience, and metrics such as visits per unique visitor, page views per visit and the percent of people who left the site after looking at just the home page (home page bounce rate) would give much more clear indicators for both sites.

….but sometimes you shouldn’t.

One of the organizations had its main site on one Google Analytics account, and its blog on another. Dan Lee, a graduate Strategic Public Relations student, noticed extremely high home page bounce rates from returning visitors compared to new visitors.

With the question of why burning in his head, Dan looked in detail at the site content and structure, and hypothesized that returning visitors were most likely to go to the home page, see the teaser about the latest blog entry, and immediately “leave” the site to go to the blog. The Google Analytics account for the blog did indeed show that its top referring site was the main site.

Google Analytics was “correct,” but only a human could have produced the right answer for the organization.

So here’s to Brian Christian for explaining how to be “the most convincingly human human,” and how the competition for the Loebner prizes continues to result in what the Economist calls “a resounding victory for humanity.” And here’s to the most adventurous and tenacious students at USC Annenberg – the journalism, public relations and business majors who took an experimental elective class with “web analytics” in the title!

E-books vs. e-readers

I was happy to see Barnes & Noble reporting digital books outselling physical ones on BN.com and Amazon announcing that the Kindle was its best-selling product ever because I hope this means much more e-reader content will become available.

I was happy to see Barnes & Noble reporting digital books outselling physical ones on BN.com and Amazon announcing that the Kindle was its best-selling product ever because I hope this means much more e-reader content will become available.

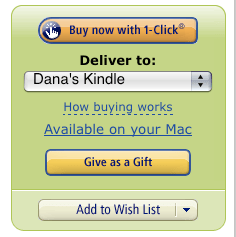

I’m always surprised and disappointed when a book I want to buy isn’t Kindle-ized. Then I’ll usually just forget about it; too bad, one sale lost.

If e-readers use is exploding, as B&N and Amazon want everyone to believe, then why isn’t every book, magazine and newspaper available in an e-reader form? Why are B&N and Amazon being so coy about releasing the type of numbers that would help publishers justify the investment?

Both B&N and Amazon have been trumpeting the number of devices sold, but this metric is meaningless, as industry watchers such as John Paczkowski at All Things Digital and Seth Fiegerman at MainStreet.com have pointed out. It’s really mysterious (or is it?) why B&N and Amazon haven’t been releasing information that would give a complete picture of the number of people who are using e-readers, the type of content they’re paying for, and the amount of content they’re buying.

Here are a few of the metrics I’d want to monitor to determine whether the audience is there to justify making e-readers a more significant part of an overall digital strategy.

Increased e-book sales will come either from current e-bookers buying more or more new e-bookers getting devices. Or both. Thus, I’d start with these two actionable key performance indicators, both ratios (not counts):

- Number of e-books sold per current registered e-book buyer

- Number of e-books sold per new registered e-book buyer

I’d focus on increasing the number of e-books bought by new e-book users, especially those who got an e-reader as gifts and thus didn’t necessarily choose to become e-readers themselves. (If you’re analytics-driven Amazon then you know this number because you’ve asked that question in the buying process.) E-readers seemed to be a popular Christmas gift in 2010; B&N sold more than 1 million e-books on Christmas day alone, according to MainStreet.com.

I’d focus on increasing the number of e-books bought by new e-book users, especially those who got an e-reader as gifts and thus didn’t necessarily choose to become e-readers themselves. (If you’re analytics-driven Amazon then you know this number because you’ve asked that question in the buying process.) E-readers seemed to be a popular Christmas gift in 2010; B&N sold more than 1 million e-books on Christmas day alone, according to MainStreet.com.

Without knowing more than this one measly number, I’m not convinced e-books are booming. Think about it. You get a Nook for Christmas, you try it out and buy a book while the generous gift giver is right there, smiling at you and saying “Isn’t it great?” Then you go on to the next present or Christmas dinner or talking to your cousin or whatever.

But how many new e-readers continued to buy e-books past the first one? (Bounce rate – one of the greatest metrics of all-time.) If they only bought one, was it because the experience was confusing? Did they just not like the e-book experience? Did they not find the content they wanted? Were they dismayed to find their favorite magazine or newspaper only puts puts part of its content in an e-reader format? (WHY do publishers do this? Oh yeah, cannibalization. Yeah, I’m going to go out and buy that print thing right now.)

But how many new e-readers continued to buy e-books past the first one? (Bounce rate – one of the greatest metrics of all-time.) If they only bought one, was it because the experience was confusing? Did they just not like the e-book experience? Did they not find the content they wanted? Were they dismayed to find their favorite magazine or newspaper only puts puts part of its content in an e-reader format? (WHY do publishers do this? Oh yeah, cannibalization. Yeah, I’m going to go out and buy that print thing right now.)

If there’s a significant drop in e-book sales from new users then you can dig deep into data that will indicate the specific actions you should take, like improving the buying process, offering incentives to one-e-book buyers in exchange for info on why they don’t buy more, and adding the content people are willing to pay for.

Because e-books are sold, there’s a treasure trove of demographic and behavioral audience data collected from the purchase process, data that gives all kinds of actionable insights about what kind of content is worth offering in an e-reader form, e.g., number of e-books sold by type (book, magazine, newspaper, etc.), category/topic, fiction/nonfiction, author, new/old.

One million e-books sold in a day? Tantalizing. Let’s see more data.

The content’s there but the data often isn’t

Neil Heyside’s Oct. 18 story on PBS MediaShift about how newspapers should analyze their content by source type – staff-produced, wire/syndicated or free from citizen journalists – got me thinking about other ways content should be analyzed to craft audience-driven hyper-local and paid-content strategies.

Most news sites have navigation that mimics traditional media products – News, Sports, Business, Opinion, and Entertainment. However, those types of broad titles don’t work well with digital content because people consume news and information in bits and pieces rather than in nicely packaged 56-page print products and 30-minute TV programs.

Each chunk, each piece of content – story, photo, video, audio, whatever – should be tagged or classified with a geographic area and a niche topic so a news org can determine how much content it has for each of its highest priority audience segments – and how much traffic each type of content is getting.

By geographic area I mean hyper-local. East Cyberton, not Cyberton. Maybe even more hyper – East Cyberton north of Main Street, for example, or wherever there’s a distinct audience segment that has different characteristics and thus different news needs and news consumption patterns.

Similarly, news orgs need hyper-topic codes, especially for hyper-local topics. The Cyberton community orchestra – not Classical Music, Music, or Entertainment. If a news org is looking at web traffic data for “Music” it should know whether that traffic is for rock music or classical, and whether the content was about a local, regional, national or international group.

Oh, and there’s one more aspect to this hyper-coding. Content should be coded across the site. Ruthlessly. For example, to really understand whether it needs to add or cut coverage in East Cyberton, a news org needs to add up those East Cyberton stories in Local News, plus those East Cyberton Main St. retail development stories in Business, and those editorials and op-eds in Opinion about how ineffective the East Cyberton neighborhood council is, and….

Sometimes these hyper-codes are in content management systems but not in web analytics systems like Omniture or Google Analytics. Knowing what you’ve got is great – but knowing how much traffic each hyper-coded chunk of content is equally if not more important.

Whether the hyper-codes and thus the data are there only makes a difference if a news org is willing to take a hard, nontraditional look at itself. The data may suggest it needs to radically change what it covers and the way it allocates its news resources so it can produce “relevant, non-commodity local news that differentiates” it, as Neil Heyside’s PBS MediaShift story points out.

Heyside’s study of four U.K. newspaper chains has some interesting ideas about how a news org can cut costs but still maintain quality by changing the ways it uses staff-produced, wire, and free, citizen journalist content. The news orgs in the study “had already undergone extensive staff reductions. In the conventional sense, all the costs had been wrung out. But newspapers have to change the way they think in order to survive. If you’ve wrung out all the costs you can from the existing content creation model, then it’s time to change the model itself.”

If a news org doesn’t know, in incredibly painful detail, what type of content it has and how much traffic each type is getting, then it’s not arming itself with everything it can to mitigate the risks of making radical changes such as investing what it takes to succeed in hyperlocal news and in setting up pay walls. Both are pretty scary, and it’s going to take a lot of bold experimentation – and data – to get it right.

Two million users? Not enough…

Xmarks had lots of users but little engagement. Apparently it forgot to figure out what the users needed or wanted.

From WebNewser:

“For the popular bookmark syncing service Xmarks, 2 million users was apparently not popular enough. Co-founder and CTO Todd Agulnick announced on the company blog Tuesday that, despite growing by 3,000 users each day, the startup was floundering and would shut down its service in 90 days….

Unfortunately, users who tried the system were looking for answers to questions rather than topical lists of sites.”

Believing in time-on-site

A Sept. 12 Pew Center study found that “Americans are spending more time following the news than over the past decade.” Great news – or is this yet another misleading key performance indicator, as my previous blog post about time spent on site might suggest?

No – I like the Pew Center study. It’s a study of attitudes and feelings. Good old-fashioned survey research (with all of its mind-numbing statistical sampling), is an essential component of web analytics. Web site traffic data is audience behavior – the “what.” News orgs have to have attitudinal research to understand the “why” so they can attract audiences that aren’t coming to their sites.

The data you get from Google Analytics or Omniture is enticing, isn’t it? (Work with me, here….) Oh wow, we can track every click! Ah, yes, we can track every click – but we can ONLY track clicks on OUR site, not on anyone else’s.

A time-on-site calculation can only be harvested for you if someone clicks on a page in your site and generates a page view that’s counted by your Google Analytics/Omniture account. Time-on-site is the time in between the first page clicked on YOUR site and the last page clicked on YOUR site.

This means:

1. If someone clicks on YOUR site and then immediately goes to another site (a bounce),

it’s not included by Google Analytics/Omniture in the time- on-site calculation. It’s like it never existed, time-on-site-wise.

It IS counted as one visit and as one page view. So that means that all of those people who come to your site regularly (you know, the ones we really like) just to get the latest on a story aren’t counted in time-on-site – and they should be.

2. If someone is on his/her third page in your site and opens another tab and goes to another site for twenty minutes before returning to your site and clicking on another two pages, those twenty minutes are included in time-on-site – and they shouldn’t be.

3. The time a person spends on the last page of your site isn’t counted.

If someone clicks through a few pages on your site and spends 15

minutes utterly absorbed in a story before leaving your site to go pay

bills online, those 15 minutes aren’t included in time-on-site – and they should be.

So, time-spent-on-site is always either over- or under-counted. And you’ll never know which – this makes this metric utterly unreliable as an indicator of success or failure. So you can’t make a decision with this data because you can’t know whether your action – a section added, the number of long-form videos reduced – caused time spent to go up or down.

More importantly, these days it really doesn’t matter how much time people actually spend on a news site. What matters much, much more is whether people are engaged with the news, whether they believe news sites are an essential component to their lives, so much so that they come back repeatedly, rate a story with five stars, leave comments, click on an ad, and otherwise use the site. It doesn’t matter whether they spend three seconds or three hours.

That’s what makes the Pew Center finding so exciting (surely you’re still with me on how great web analytics is?). People actually said they’re spending more time with the news now than they did a decade ago. It doesn’t matter whether they actually are (!) – they believe they are.

I wish every news org could afford its own Pew Center-like attitudinal research study so it could track how engaged its own targeted audiences are (or aren’t), and to understand how to get and retain new audiences. The information wouldn’t always be pretty, but at least it would be data that could make a difference.

Decision-making with data

Wow – a web analytics story in the New York Times! And one that probably didn't spark mass hysteria by saying that looking at web traffic data is the end of journalism as we know it.

Jeremy Peters' September 5 story, "Some Newspapers, Tracking Readers Online, Shift Coverage," nicely framed the issues about using web analytics to make decisions about coverage. At one end you have journalists who completely ignore audiences and report whatever they want. On the other there are those who "pander to the most base reader interests."

This was one of the few mainstream media stories I've seen that recognized the new role that audiences have in informing – not dictating – news decisions.

Actually what was the most interesting to me was that Raju Narisetti, the Washington Post's managing editor of online operations, said that he used "reader metrics as a tool to help him better determine how to use online resources….the data has proved highly useful in today's world of shrinking newsroom budgets."

In other words, Narisetti didn't just look at overall site traffic numbers like total visits or unique visitors and say "Oh, that's nice," or "Whatever! I've got a paper to put out." He had to cut his budget, he saw that long-form videos had little traffic compared to other types of content, and then he decided to cut "a couple of people" from that department.

Narisetti made the decision – the data didn't. He used the data. In my rather narrowly focused web analytics world that is a really, really big deal. Data just wants to be useful. Seriously. If it could talk, it would say that it doesn't want to be any part of a daily e-mail "about 120 people in The Post's newsroom" get that lays "out how the Web site performed in the closely watched metrics – 46 in all."

Forty-six!

For data to be useful you have to ask it specific questions that you know it can answer. A metrics report won't tell you what department to cut, and by how much. However, it could tell you what types of stories get the most and least audiences, and which story types appear to have growing or declining audiences. You can also get indicators – such as the percent of long-form videos people watched to the end, rated and/or commented on – of whether you're engaging audiences.

Then the hard part – the decision – is up to you.

Number wars

What does the war in Iraq have in common with the war news organizations are fighting for their survival?

Nothing at all, unequivocally.

However, I was struck by Owen Bennett-Jones’ closing of his August 27 BBC story about the disparities in the reports of the numbers of civilians killed in Iraq since the war started in 2003:

“It remains true that people tend to cite a number that reflects not their view of the quality of the research but rather their view of the war.”

In other words, getting someone to use your numbers – your definition of success – is just as hard as getting them to change their thinking.

In the world of web analytics, people “tend to present the metric that’s most likely to work in their favor. They’re tracking the wrong way or they don’t want to look at a particular set of data. They are wrongly using analytics as what [Robert Rose of Big Blue Moose] calls a Weapon of Mass Delusion….Worst of all, they are not learning to apply insight to action.”

— from “A Web Analytics Trap,” by Jim Ericson, Information Management, August 13, 2010

Page views: bad metric #3

Why do news organizations persist in using total page views as a measure of success? Perhaps because if you're afraid of numbers then you're even more afraid of bad numbers, or numbers that tell you that your site isn't as successful as you want.

As with unique visitors and time on site, page views is a deeply flawed metric for understanding how a news organization is growing and retaining audiences.

If the number of page views goes up, it could be a good thing. Or, it could be bad.

If page views go down, it could be a bad thing. Or – you guessed it – it could be good.

We would all like to think that a soaring number of page views means lots of people are eagerly pawing through our sites reading everything that's written. However, how many times have you gone to a site and clicked on, say, 12 pages, fruitlessly looking for something?

This is counted as:

1. One unique visitor

2. One visit

3. 12 page views

And one dissatisfied person who may not come back.

The page views metric rewards the bad design and navigation that many news sites have (sorry). Most news sites persist in using section titles that are the same as their legacy media product (e.g., "Local News," "Life"), leaving audiences – if they're so inclined – to have to click numerous times before landing on a story about a particular city or activity like gardening.

Or, a site breaks up a story into multiple pages, which can be annoying to a reader and reduces the possibility the reader will read the entire story and rate it, e-mail it or leave a comment. What could be counted as one page view with a comment is counted as, say, five page views.

If a site is redesigned and readers can find what they want with fewer clicks, total page views will – should – go down.

And, dynamic content, or content that changes on the page without the reader clicking anything – isn't counted at all. Streaming stories, videos, widgets, Flash applications, podcasts? One page view.

To truly grow, a news org must understand every action its audiences are taking on its sites. These are challenging times that require news sites to experiment and try many different things. Not all things will work, which means sometimes the numbers will be bad. But – you guessed it – that's a good thing. We have to know if something's not working so we can fix it.